The Mists of Time

The Mists of Time...?

Aristasia's pre-internet history is murky at best, and many accounts seem to contradict each other.

Speaking as someone formerly involved, it often feels as if Aristasia, like Batman’s Joker, has a multiple choice past, sadly - we’ve learned not to trust what we’ve been told, and are slowly learning what really happened - all the while seeking to figure out the how and (perhaps more importantly) the why of it all.

This page tries to piece together what I am able to about Aristasia prior to, or in the early days of, their online involvement. It also includes information about Aristasian precursor groups such as Rhennes and St. Bride's School. I was never involved in any of these precursor groups, nor pre-internet Aristasia. I was born in the late 1980s, long after Rhennes, for example, and my only contact with Aristasians has been online.

My involvement was between 2000 and 2010. A lot of this page relies on archival information, some of which wasn't available until after I'd left Aristasia. Some of it really changed how I saw Aristasia, as you'll see.

Oxford?

When I first discovered Aristasia online circa 2000-ish, I was about thirteen, and not all that good at research. This problem was compounded by the lack of resources available at the time - a lot of material just simply hadn’t been digitized. Nevertheless, I was eager and curious to know as much about Aristasia and its history as possible.

The Aristasians, both on their public websites and in private, mentioned a particular book by Mark Sedgwick, entitled Against The Modern World: Traditionalism and the Secret Intellectual History of the Twentieth Century. This book is exactly the kind of large, expensive academic tome that a thirteen-year-old girl in the rural midwest had no hope of finding back then. The Aristasians cited Sedgwick as referencing the inception of their own movement:

Aristasia is the post-1980s name of a group which, in slightly different form, was earlier known as The Romantics and The Olympians. It was started in the English university city of Oxford in the late 1960s by a female academic who used the name of “Hester St. Clare.” St. Clare was born in the 1920s; other details of her career are unknown. A Traditionalist, in the late 1960s she began to gather a group of younger women, mostly Oxford students, who were dismayed by the “cultural collapse” of that decade. They took Guénon one stage further: worse even than modernity was the “inverted society,” the postmodern, contemporary era produced by the cultural collapse of the 1960s, an event often referred to by Aristasians as “the Eclipse.” Inverted society—often referred to as “the Pit”—stands in much the same relation to modernity as modernity stood to tradition, argued “Alice Trent,” St. Clare’s most important follower. Not all that was produced before the Eclipse was worthless—Beethoven and Wordsworth are clearly not “malignant aberrations,” for example. Each phase in the cycle of decline may produce developments that, while “of a lower order than was possible to previous phases, . . . nonetheless are good and beautiful in their own right.” Nothing produced after the Eclipse is of any worth at all, however (though theoretically something might be). In practice, all in the Pit is inversion—“the deliberate aim is an inverted parody of all that should be.” The higher classes imitate the lowest, “family life and personal loyalty” are replaced by “a cult of ‘personal independence,’ ” and even the earlier achievements of modernity are lost, as crime and illiteracy increase. Chaos is preferred to harmony in art and dress, and masculinity replaces femininity.

Mark Sedgwick, Against The Modern World: Traditionalism and the Secret Intellectual History of the Twentieth Century, Pages 217-218

Sedgwick’s 2004 book focused on Traditionalism broadly as a movement. This included small groups like Aristasia that were inspired by Traditionalist philosophers. While I didn’t have access to the book at the time, even quotations from it were a lot to take in as a teenager. They underscore the importance of the works of René Guénon in the Aristasian project. It seemed odd to me (as a teen) that Guénon would get mention at all - he is, after all, male. Actually looking at his beliefs makes things a bit more clear, though…

René Guénon himself wasn’t particularly concerned with enterprises of the Aristasian sort - I’ve no clue how he would’ve felt about ladies roleplaying as college girls in an alternate universe. A French writer in the early 20th century - he mostly focused on metaphysics and intellectual history. Guénon was known for blending (the - let’s be honest - white, early 20th-century variations of) Hindu and Buddhist esotericism with a fiercely anti-Modernist perspective on the Western world. Guénon believed in a primordial philosophy - a deep abiding truth forming the bedrock of all (real) metaphysical systems.

He believed that Modernity had sought to divorce the Western world from this underlying (decidedly spiritual) reality, confusing us with materialist lies. Guénon converted to Ṣūfism later in life, and died in 1951 - long before the Aristasian project began, one way or another. The Aristasians share his general view of the modern West as a place of spiritual malaise, and also share some of his proposed remedies - the concept of a primordial philosophy. To an Aristasian, said bedrock of truth takes a decidedly feminine flavor - and we don’t see that in Guénon himself. Still, it is easy, I think, to see how Guénon influenced (or completely inspired) some of the Aristasian corpus of thought.

On forums like the one shown in the screenshot above, a similar story was told by the core membership:

Aristasia-in-Telluria was a very private arrangement in its earliest days, with no formal name or organisation. It went by various nicknames such as The Olympians, and even The Mob (a term coined when two, or perhaps three, groups of Aristasians arrived at the same venue at the same time in black Trentish cars, prompting the comment that they looked like the mob arriving in a Trentish film).

The lady credited with being the founder of Aristasia was Miss Hester St.Clare, though it was actually a phenomenon that emerged out of a group of women at Oxford, to whom Miss St.Clare was a sort of intellectual mentress.

Aristasia (or, to be strictly accurate, proto-Aristasia-in-Telluria) had its own "parallel university" of Milchford, and the first seceded Aristasians were girls who discontinued their official studies at Oxford to become full-time Milchford undergraduates.

Miss Snow began to write a novel about the early-ish (though not eariest) days of Aristasia at Milchford, but this was discontinued for personal reasons. It is possible that we may be able to publish parts of her manuscript in Elektraspace in the future.

Lady Aquila in a 2005 (screenshotted) forum post

This is a very interesting image, and was tantalizing for me as a youngster. They, of course, didn’t know how young I was, and would’ve booted me if they had, but as a teenager, I loved all things associated with the classics and the great universities. Had I been born a few decades later, I’d likely have jumped into the Dark Academia trend. And, back in 2005, it seemed as likely as any explanation for the movement’s origins.

Oxford itself has always had a long history of birthing strange and interesting movements, people, and things. Part of this probably just owes to its association with wealth and the leisure to explore provided by that. In any case, given that a milch is a (female, obviously) dairy cow (versus an ox which, well, male), we can see why these early Aristasians could’ve named this parallel university Milchford.

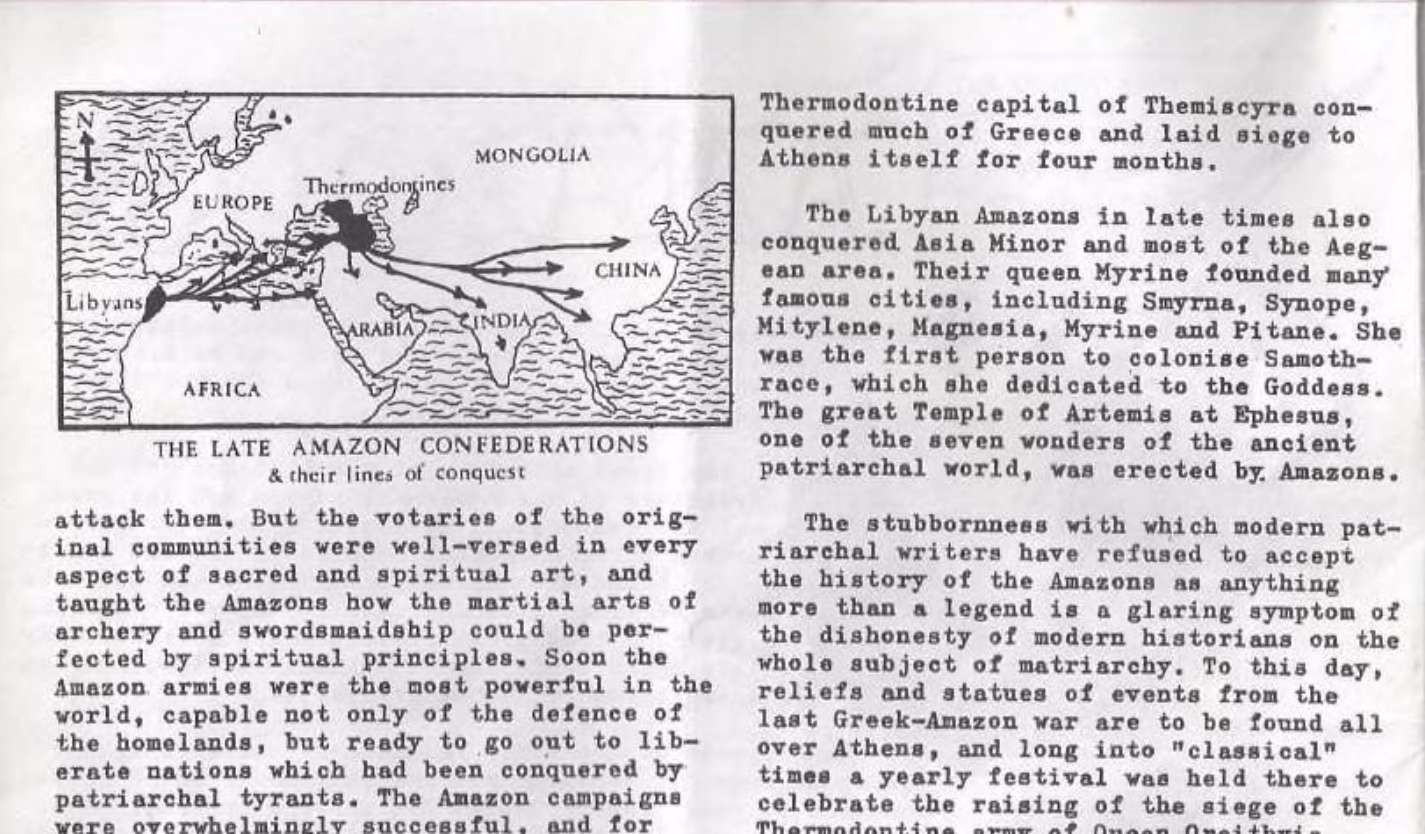

A screenshot (preserved by @Tellurian-in-Aristasia’s blog) gives us a peek at an interview between Alice Lucy Trent (author of The Feminine Universe, regarded as Aristasia’s primary philosophical manual) and an unnamed Tellurian (worldly) academic. One might assume that said academic is Sedgwick, but the name isn’t given. Miss Trent talks about having the privilege of introduction to Hester St. Clare’s circle while studying at Oxford. The brief snippet suggests St. Clare was born in the 1920s, and even goes as far as to float the idea that Aristasia has an “Oxonian” flavor overall at times.

There is, though absolutely no evidence that any of this happened, which weirdly makes me quite sad. “Hester St. Clare” was said to have been a pen name, making the original mentress of this group impossible to research like many of the individuals involved in this. Try as we might, currently, those interested in Aristasia (having the whole of 2023 digitized resources at our disposal) have sought the early Aristasian connection to Oxford University in the 1960s - but it may well just not be there.

It’s likely, and this I believe, that one or two early Aristasians may have went to uni or at least taken a few classes at Oxford. Plenty of movements like Aristasia did originate in that kind of environment after all, or just amongst university-aged folks. Guénon himself wouldn’t have been an unusual topic for a crowd like that, either.

That said, I am incredibly skeptical of St. Clare’s existence, as well as the entire story of Milchford, though. Why? For one thing, I highly doubt a group of Oxford academics who chose to secede from not just Oxford, but the modern world, would’ve gone unnoticed by academic history, particularly with the involvement of René Guénon’s work.

I would expect it at least see some references to disagreements amongst colleagues at the time, or some contemporary discussion of it. I get that an absence of evidence doesn’t automatically mean something wasn’t there, though.

Regardless, we don’t see many references to Milchford, though, prior to the Aristasians themselves telling the origin story in the 1990s and 2000s, and certainly none from non-Aristasian sources. You can’t really count Mark Sedgwick’s book as a credible source for it, unfortunately - he seems to have just interviewed the Aristasians and accepted their version wholeheartedly.

This wasn’t uncommon for journalists and authors in that era studying small marginal movements like this. I’m not saying Sedgwick isn’t a good scholar on other aspects of traditionalism - he may well be; I’m not knowledgeable enough to be sure.

It’s worth noting that in the early 1990s (long after the Milchford era was said to have occurred), some Aristasians and Aristasia-related groups did exist in the city of Oxford, as evidenced by this Sunday Telegraph article. That article paints a much less-rosy picture of the movement than the one I was given of the alleged, earlier Milchford group.

As always, this site is a work in progress, and anyone with anything to add to this is welcome to contact me.

Lux Madriana

The Ekklesia of our Lady is not just a group of human beings on this earth. It is a vast and timeless family arrayed through a11 time and space. It includes the Geniae or angels - the intelligences of the highest spheres, the perfected heras or saints who have passed beyond the wheel of birth and death into pure Enlightenment, as veil as nature spirits and creatures on countless worlds and levels of being, who have remained in harmony with the primordial Law and way of life laid down by God Herself from the dawn of time.

A person cannot become a part of this family by a merely theoretical attachment to the Path, for Madrianism is infinitely more than a mere belief. It is a golden chain that leads from the very summit of heaven to the deepest valleys of the earth, and every maid who will return to the harmony (themis) of legitimate earthly life, according to the Way laid down by Inanna Herself, must take up her position as a link within that living chain, binding herself in love and obedience to the celestial hierarchy in its earthly manifestation. It is necessary that she should meet with her earthly sisters and become a part of their community; and when she is ready and has a sufficient understanding of the primordial Truth, she vill be ritually offered to our Lady, which will make her a full member of that family.

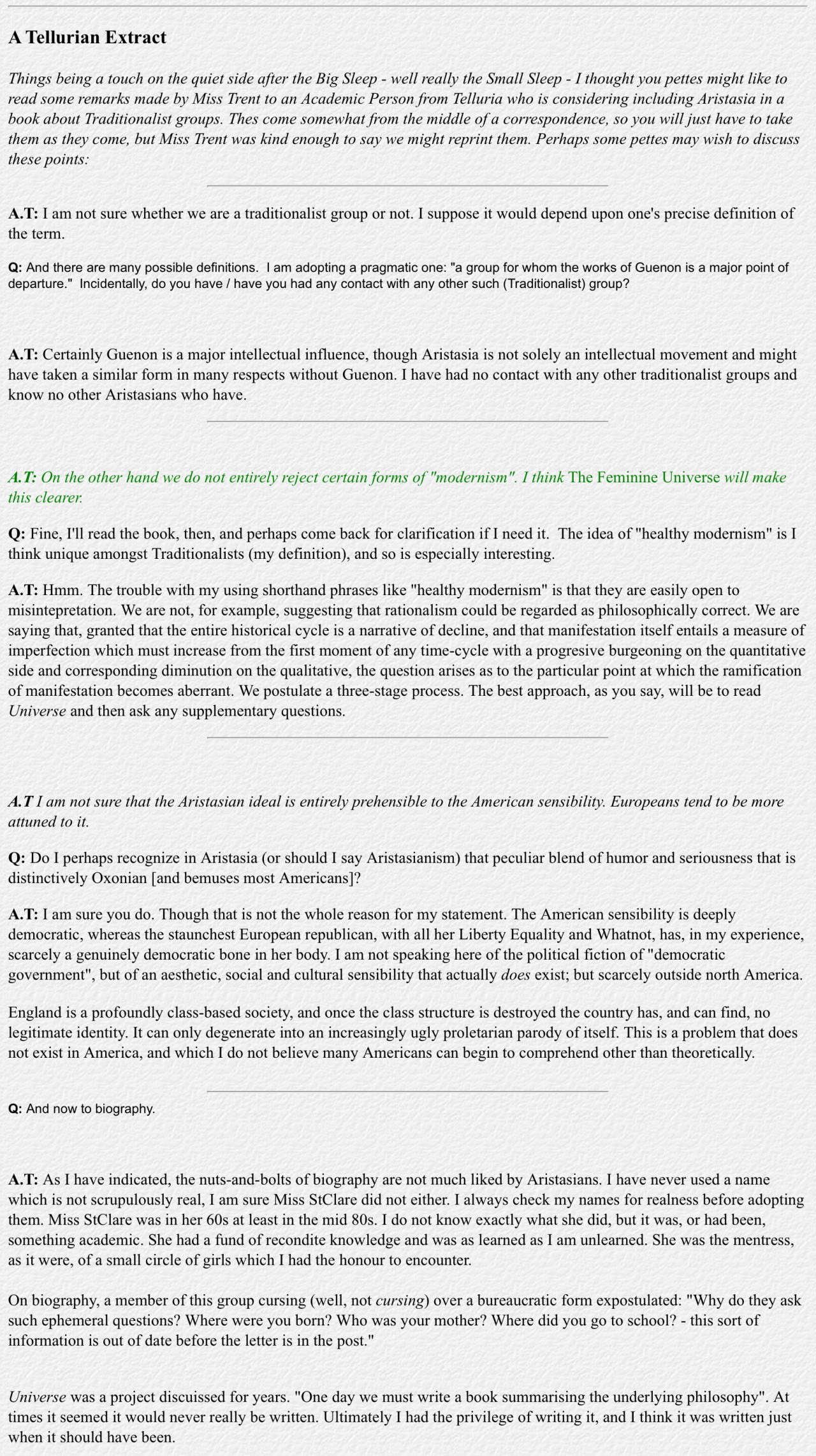

The Coming Age, Volume 12, published by the Madrian Literature Circle in the late 1970s.

The earliest publications that feature the inception of Aristasia’s intricate worldview are those published by the Madrian Literature Circle. This organization operated in the late 1970s and early 1980s, before Aristasia, Rhennes, St. Bride’s School, and predating almost everything on this page, really.

Called Lux Madriana or Light of the Mother, this group seemed to have been significantly larger than the later incarnations. A schism seems to have occurred within Lux Madriana (or, at very least, its earliest precursor) prior to some members departing due to matters of gender and sexuality. At least, that is what has been alleged.

I, as someone born quite afterwards, and piecing things together from clippings, can hardly comment on the why and wherefore of this schism, whether it was done “badly” as some online have said or not. By most accounts, though, it was a poor experience for all involved. This site collates some quotations from Madrians and those adjacent to the situation, painting a rather negative picture of (what became) the Aristasian precursors.

“They were strongly influenced by the lesbian separatist ideas around that time and the ones, only 2, I believe, who were lesbian remained, cut themselves off from everyone who were their loyal supporters and adherents, and dropped everything they had built up, under the hand of the Goddess. This was badly done, some people still want to rake over the past but I want it to be left and for us to look forward and move ahead. What they are doing now, the 2 women, is deceitful, and dishonourable, they are ensnaring young women whom they use for their pleasure. With Jennifer there was always a strong element of fantasy which is not healthy. I haven’t looked at what they are saying because I’d be too angry, but it is all complete nonsense.”

Alleged on this site to be the words of Madria Olga Lotar (Founder of Ordo Rosa Ekklesia Madriana), writing on a mailing list about Déanism at an unspecified time, likely post-2000.

The “two women” (though I suspect there were more, in actuality) who remained kept the name Lux Madriana for some time after this; the others (apparently) did not, as Madria Olga’s title indicates. It is this group, though, the “lesbian separatists,” who would ultimately lay the foundations for what became Aristasia, as one might expect, and were the ones who began endeavors like St. Bride’s School.

While much of the Madrian Literature Circle’s published documents themselves appear on the Internet Archive in passably high-quality scans, this outsider’s perspective from Womanspirit Magazine is awfully interesting too, don’t you think? It was written in 1983, after the schism, weirdly enough.

Given the length of time since it’s publication, the subject matter, and such, I don’t feel untoward providing the full scan and quoting it below for those not wishing to squint at old text.

On the feminist spirituality scene there are very few groups that could be said to have "organised religion"--except for those which are based on witchcraft, better described as "organized magic." Most womanspiritual groups are informal in their theory and practice, and most largely accept the world-view prevalent at the moment. Feminist spirituality is distinctively "of our time" in many ways, and in general eschews more traditional duality. concepts of spirit- As far as I am able to discover, there is only one group practising a traditional type of Goddess religion, and they claim it in the literal sense of the word--"tradition, that which is handed down."

Lux Madriana ("The Light of the Mother") appeared in round about 1976; this is the "public relations" wing of the religion, which calls itself the Rhennes (derived from Rhiannon, the Indo-European Goddess). They claim that their doctrine and practice have been handed down from the remotest age, often in secrecy and under persecution. However, this is not a religion which one can take on and then live out one's life in the modern world. Madrianism is a total way of life (possibly the nearest comparison might be the old Amish of America) reflecting the fact that Madrians do not separate "sacred" and "secular." Every least activity takes place in a ritual context and is related to a sacred framework--the structure of the community reflects the divine order, and all crafts are considered a ritual pathway. Modern technology is shunned as far as is practically possible, because its products are divorced from any sacred intention or meaning--unlike those of "primitive" societies, which have an inherent spiritual significance.

The Madrians worship a triple Goddess; the Dark Mother, standing before all existence; the Bright Mother, who is "breathed forth" by the Dark Mother and from whom everything emanates in an original perfection, and Her Daughter the Maid, who sustains existence by a primal sacrifice of Herself. The triple Goddess is one Goddess. Madrian thealogy is rich in a variety of image and symbol, and provides for a range of individual temperaments in much the same way as Hinduism. There is no male divinity; the feminine principle is the spiritual principle-divine, creative; the Absolute-and the Goddess is self-existent and complete in Herself. The masculine principle of the cosmos is partial, dependent on the spiritual pole for its existence, and is the material element. Every individual thing exists on a sliding scale between the feminine and masculine principles. Although in Madrian society women have the authority, men are not oppressed second-class citizens as women are in patriarchy--the essential difference between female rule and male rule is qualitative.

There are several matriarchal scriptures, again said to be handed down from the immemorial past; the Creation, the Mythos of the divine Maid (telling the story the teachings of the Daughter. death and return of the Daughter) There is also a question-and-answer catechism of basic beliefs. The year follows a cycle of feasts and fasts, a sacred calendar of thirteen lunar months, the pattern of which reflects the eternal Divine Drama. There are many rituals, including the Rite of Sacrifice, where a honey-cake is offered to the Goddess and a cup of wine shared by the participants; all women perform this rite. The priestesses conduct a Communion rite, as well as initiations and a wide range of magical rituals, some highly occult and intended to restore the cosmic balance. Vows of obedience to the priestesses and others constitute an essential part of the spiritual and social organization. On the personal level the spiritual aim is union with the Goddess; the practices of prayer, chanting and the recitation of a kind of rosary are considered vital.

Needless to say, there are plenty of people ready to criticize Madrianism, some of their objections evidently fantasy based on a misunderstanding or garbling of Madrian belief, for some of them more than mere rumor, for there is no smoke without fire! and some of them more than mere I have actually heard people calumiate the Madrians without having read a single word they write. Although I am not a Madrian, nor have I any intention of becoming one, my personal view is that the cult fulfills an important role, providing a ritual and contemplative framework and a form of spirituality which is not found elsewhere in the Goddess-movement. I find the Complex way, and their world-view satisfyng beyond complex way, and what is expounded anywhere else in the Goddess move-ment. But while theory may be sound, practice is another matter; moreover the claim to be an ancient tradition may or may not have a basis in truth. hope that by this article some understanding may be fostered, and some women may find in Madrianism the kind of spirituality they are seeking.

The Madrian magazine "The Coming Age" is highly recommended; details of this and other publications can be obtained from Lux Madriana, An Droichead Beo, Burtonport, Co. Donegal, Eire; please enclose an international reply coupon.

Janet McCrickard, Womanspirit Magazine, 1983.

As you can see, Ms. McCrickard is relatively sympathetic to the Madrians compared to some sources, but willingly admits (or alludes) to fire in the presence of smoke. Is she talking about the controversies (already extant) regarding possible fascist connections, or something else? It’s hard to say. At least, unlike the British Broadcasting Corporation’s news clips from the time, this piece actually questions the Madrian narrative about their religion being an ancient tradition.

There is zero (overt) talk of their fascist connections, interest in physical punishment, or much beyond the theology (er, thealogy, perhaps) of the Clear Recital (Madrian Scriptures).

Ms. Crickard seems to have read their writings, perhaps the scriptures, or at least implies she has, or at least more than a passing familiarity with the group. Her positivity is thus a bit odd, considering that even in those days, the Madrians weren’t terribly good at public relations (much like later Aristasians) and had already been tarred with plenty of unsavory associations. It’s possible Ms. McCrickard simply wasn’t aware of how much fire (as she put it) there actually was, though, having only seen puffs of smoke.

It’s also worth noting that, judging by the address at the bottom of the article (and the date), it was written after some of the group had broken away and moved to Burtonport.

In other words, Ms. Crickard’s article specifically refers to the Madrians who ultimately became Aristasians, rather than the earlier community, nor those who’d parted ways with the Burtonport girls and gone silent. I would speak more on that group (the older Madrians, who split ways with the Aristasians), but frankly, I’ve little knowledge of what they got up to - those ladies were terribly private.

Other responses to the Madrian Literature Circle were less positive and did highlight some of the more disturbing aspects of the groups already-existing theology.

HEIL LUX MADRIANA

I notice that you have an advertisement in several issues of your magazine for a religious organisation known as Lux Madriana, describing themselves as "the matriarchal tradition. .. the spiritual feminist alternative". Others beside myself are very disturbed to see this advert in the pages of your magazine because this religion is in fact yet another form of fascism. It preaches obedience to an authoritarian hierarchy, it is against the fundamental rights of free speech and thought, and expressly denies equality, democracy, sexual freedom-indeed all the freedoms that publications like Peace News stand for. (The last two issues of their magazine make this position quite clear.) I am sorry to appear intolerant, but I feel that someone ought to speak out about this.

Yours sincerely and angrily

S Butler c/o Peace News 8 Elm Avenue Nottingham

A clipping from Peace News, featuring an early call-out of Lux Madriana for their authoritarian perspectives.

Lux Madriana (as a new religious movement) formed the spiritual basis for Aristasia (and later precursor groups). It ultimately became Déanism, Filianism, and the Janite Traditions therein, which persist in small cybersects to this day. Most present-day Déanists are not fascists, and have tried to distance themselves from earlier groups. I’m not sure why they haven’t coined newer, less utterly-loaded words for their beliefs. Much like Thelemites with Aleister Crowley’s “holy books,” they tend to either ignore or reinterpret those portions of the Madrian scriptures that are genuinely disturbing.

These scriptures are sometimes referred to as the Gospel of God the Mother, but the phrase Clear Recital is used more frequently nowadays. These scriptures describe the story of the Daughter’s descent into the underworld, but quite plainly lay out the restrictive nature of the Golden Chain embedded in these beliefs, and the obedience (apparently) expected by Madrian priestesses, and an intense hierarchy, too.

Let the brother obey the sister, and the younger sister obey the elder. Let the child obey the mother and the husband obey the wife. Let the wife obey the lady of the household. Let the lady of the household give obedience to the priestess; let the priestess give obedience unto Me. Let the maid obey the mistress, let the pupil obey the ranya. Thus shall all things be in harmony and harmony be in all things.

The Eastminster Critical Edition of the Clear Recital, published in 2021, page 62. Apparently “harmony” here is just gender-flipping normal systems of oppression…

Initially (in the 2000s when I was heavily involved) these scriptures were only available online or printed by the Aristasians themselves via on-demand publishing. Sun Daughter Press, their remaining publishing house, still sells copies on Amazon. When I originally purchased the scriptures almost fifteen years ago (the SDP edition), the notion of the Golden Chain vaguely appealed to me. I read it as speaking to a maid’s need to root herself within the overarching structure of reality, to be part of creation rather than atomized from it, and thus more open to love, divine or otherwise.

This might’ve been an intention on some level for some practicing Madrianism, but for most, and certainly for many Aristasians, the Golden Chain was simply that - a chain. And a chain is a leash, and a leash is restrictive, even if it is God-given and golden. Perhaps if the Madrians were, in fact, right in their thealogy, I’d face Déa upon my death and walk backwards into the Underworld, refusing the chain?

Do you think the Clear Recital’s Golden Chain is about restriction, community-building, hierarchy, fascism, or religious devotion? Draw your own conclusions from perusing one of the most popular editions (and there are many) on Archive.org, compiled into a rather easily-read format. I’ve made my perspective clear, though…

Oh, and about that 1983 schism? The one that separated the proto-Aristasians from the rest of the Madrians? What happened to the others, the ones who didn’t end up leaving and becoming Aristasia? I heard (as described here) some rather wild stories initially from guys on AOL about them having been decimated by “occult warfare,” possibly involving Baphomet. I figured that part was nonsense, but did assume the group had dissolved. All my Aristasian friends never mentioned a real “schism,” - they just described Lux Madriana as a precursor to Aristasia with a spiritual focus. They implied it had fully evolved into Aristasia and didn’t exist in its original form.

This wasn’t true. It seems that the other Madrians practiced outside of the Aristasian milieu for decades. As far as I know, there are (very private) practicing Madrians (without an Aristasian connection) to this day. If you are one of them, feel free to message me with anything you’d like added, corrected, or to inform me of what might be missing or overlooked. I doubt it, because most say Madrians don’t talk to just anyone, but I’m extending the offer.

Rhennes

In September of 1982, a group moved into an already notorious building in Burtonport, County Donegal, Ireland.

A group of women have come to Donegal to set up a sanctuary from the modern world.

The Silver Sisterhood, also known as Rhennes, arrived in Burtonport, Co Donegal in September 1982 from a small town in Yorkshire. They call themselves Rhennes in honour of a mythical goddess who was half maid, half-mare. They have their own language, music and a deep tradition of crafts in a pre-mechanised lifestyle. They wear full-length dresses and shawls and keep their heads covered when in public.

From the Raidió Teilifís Éireann archives, November, 19 1982.

This Irish public radio program interviewed some of these maids to get a clearer picture of how they were living now, as well as the origins of their lifestyle.

The Rhennish tradition is the most ancient religious and cultural tradition in New Zealand, that is to say in Britain and in Ireland, and we worship God as the mother and everything we do is centred around that worship.

Sister Angelina of the Rhennish Commune, speaking to Raidió Teilifís Éireann, November, 19 1982

The above video shows a brief news snippet about the group, so give it a watch. That autumn was a busy one for these Burtonport maids. They also created a document called The Book of Rhiannë, outlining their beliefs, religion, and lifestyle.

It was published as a supplement to The Coming Age, an existing regular newsletter. The Coming Age spoke for Lux Madriana. They, in turn, were said to be the new, open incarnation of this previously secretive British matriarchal tradition, the Rhennes.

The Rhennes, or Silver Sisterhood, perhaps, and their strange mare goddess had haunted the British isles for some time, apparently.

We are the Rhennes. Our symbol is the white mare. From time untold we have inhabited the islands at the far west of the world. Once we ruled a mighty Empire in Northern Europe — part of the world’s last greet matriarchal civilisation. For centuries we held the patriarchal barbarians at bay, keeping the northern world safe for civilisation; but eventually we wore driven back to the island strongholds of the Rhenneland. When Mider, the first patriarchal king, ensconced himself in these islands, our daring, dashing Queen Colwyn smote him down again. But the decline of the Iron Age is inexorable. In the end we were defeated in England and at length even our fortresses in the west of Ireland were overrun. For centuries our religion was outlawed and we faced increasing persecution. If power and tyranny and ruthlessness were enough to destroy a tradition, then matriarchy in these islands would be a thing of the past, crushed out of existence centuries ago. But we are the Rhennes, and we do not know the word surrender.

From generation to generation our tradition has been past down, always in secrecy, and often in direst danger. We live according to *Themis, the law of the primordial Tradition. Maids are the heads of households and leaders of the community, and all the important aspects of life are carried on as they have been from time immemorial.

But what sort of people are we, we Rhennes?

The Book Of Rhiannë, page 12, published January 7th, 1982.

Above, note the asterisk aside the word Themis. Earlier in the book, it’s explained that the Rhennes have their own language (Rhennish, appropriately, enough).

They preferred to keep certain, more sacred words within this language a secret; thus these get replaced by a corresponding word from another culture. Here, Themis replaces a Rhennish word. Since the next page describes Themis as Cosmic Harmony, well… I wanna guess that the word is being used as a gloss for Thamë, the typical Aristasian/Raihiralan word for the same concept.

What follows after that is “A Rhennish Childhood,” a short essay where a maid describes growing up in amongst the Rhennes. Her first memory is a devotional statue lit by dish-lamp. Her mother was called a “Ranya” in her craft (woodworking).

The author equates this term “Ranya” with “that of an eastern guru.” This is exactly how the term “Ranya” gets used in Aristasian Raihiralan later on, of course.

Most of the piece described how the narrator’s mother and father relate to one another within the context of matriarchal marriage, and it’s a relatively short read. The narrator expresses a great degree of hostility towards “Babylon,” (ie, the outside world), and much is made of how confusing Rhennish people find that.

A portion of The Book of Rhiannë was devoted to discussing the Silver Sisterhood’s work in Burtonport itself, of course. The house in question was called “a matriarchal village under one roof.” An Droichead Beo was given a name meaning “the bridge of life” in Gaelic “because a large proportion of the Noyarhennya were Irish or of Irish descent.”

The book itself showed an image of the house with the caption “THE BRIDGE: a magic gateway.” Maids, they said, were welcome to come and learn Rhennish matriarchal spirituality and philosophy that had previously only been transmitted behind closed doors.

The Coming Age

PROBABLY THE MOST difficult question for а Madrian to answer is the one that she is most frequently asked: “What is Madrianism all about?” After all, Madrianism is not just a ‘religion’ in the limited modern sense of the word: it is an entire way of life ав well as a total philosophy which embraces every aspect of manifest existence.

The Coming Age, Issue 15, page 2, from 1980

The Coming Age, the newsletter that had published The Book of Rhiannë, had been revealing their matriarchal philosophy and metaphysics since the late 1970s. It covered matriarchal prehistory, seasonal holy days, nature spirits, reincarnation and many other similar subjects. You can read many issues of The Coming Age right here on the Internet Archive, mostly tagged “Lux Madriana.”

You might wonder, though, why a group that seemed to shun the modern era (leading a “pre-mechanised lifestyle,” according to the press), would speak of a coming age. This dealt with their cyclical view of time. Like the Aristasians, they believed human history was a tale of degeneration from a primordial Golden Age.

Early civilizations were peaceful and matriarchal. Each world-cycle would end in a tumultuous patriarchal Iron Age, only for the world to once more renew. We now inhabited just such an era, of course. The coming age they awaited was that future renewal of the primordial matriarchy.

THE LAST five or six thousand years have constituted Kali Yuga, or the Age of Iron; the tail end of history, in which the supernatural light in the heart of humankind begins to fail.

The first millennia of the Iron Age saw the decadence of the old matriarchies and the gradual encroachment of patriarchal and semi-patriarchal forms of society and religion. The Madrian faith and matriarchal order which had been the basis of human life for untold ages was beginning to give way to a cruder religion and a harsher way of life which would lead eventually to the violence and materialism of the modern world.

The Coming Age, Issue 11, page 2, from 1979.

Several issues of The Coming Age deal with the topic of the Amazons - warrior women who, they say, made a last stand against patriarchy in the Mediterranean. Much of this draws from existing legends (from Greece) about the Amazons, but plenty seems to come from thin air of course. The Coming Age, though, argues that much of this history was suppressed for patriarchal reasons.

If all this evidence referred to anything else, it would simply be regarded as an ordinary piece of history. Nothing but the ingrained prejudice of patriarchy has ever cast the smallest doubt upon it, One is reminded of an incident in which an official of a well known photographic company was asked to certify that there was no evidence of forgery on the famous Cottingley fairy photographs. Having examined them, he said "I can't do that.” "Why," he was asked, "Is there evidence of forgery?” "No." "Then why can't you give a certificate?" "Because they're fakes." "How do you know that?" "Because there's no such thing as fairies,”

The Coming Age, Issue 11, Page 3, from 1979.

Rhennish Outta Nowhere

They have their own written language, a thriving musical tradition, and a deep culture and spiritual involvement with traditional crafts and a pre-mechanised lifestyle.

From The Irish Press, Monday, May 9th, 1983

Articles in newspapers described An Droichead Beo, the Rhennish group in Burtonport in those kind of terms, calling it the first open Rhennish household in a millennium. Mostly, they just quote the members themselves. Some take the panicked tone of the threatened mainstream, to be fair.

The same article mentions Rhennish belief in fairies amid a flurry of other attempted “shocking” revelations about the movement, positioned over another article about a “scary” new religious movement. These initial critical articles placed the focus on the group’s sheer oddness, strange beliefs, or the supposed threat posed by occult beliefs.

All of these articles, even the critical ones, leave out a key piece of information about the Rhennes, though: none of what the Rhennes claimed about their history was true.

If one isn’t versed in the history of paganism and especially in recent religious history, you might not at first glance realize how utterly fabricated their claims were, though. There isn’t a language called Rhennish from the 14th century that they could’ve been speaking. I discuss this a little further on my page about Aristasia’s language, Raihiralan. Raihiralan and Rhennish are extremely similar, if not identical.

The world was never a universal, matriarchal golden age, though the Aristasians, like the Rhennes, believed this. That idea came from 19th century writers like Eduard Gerhard and Arthur Evans, who made a lot of assumptions. I hate to use Wikipedia of all places as a summary for such a huge, academic subject as this, but you can read a bit more about the “Great Goddess hypothesis” on there. Check out the sources there for more on the topic. Aristasia’s own beliefs about prehistoric matriarchy are explored here.

You won’t find any archeological, historical, or other records of Rhennish culture, and this likely isn’t because they were simply that well-hidden for thousands of years. Quite simply, the Burtonport Rhennish, and their whole culture, appeared out of nowhere, albeit with a full “origin story” that rang true enough for the press.

To return to the question posed by The Book of Rhiannë itself, “What sort of people are we, we Rhennes?” From all this, I can only suppose they were the sort of people who didn’t let the facts get in the way of whatever they were doing…

A Pagan Precedent

This kind of fabricated backstory isn’t actually unusual in the history of new religious movements in the mid-20th century. I’m not only referring to the obscure ones, either. It probably isn’t unusual in the history of ancient religions and spiritual movements throughout history in general as well, but I can only speak to what I know. Anyways.

Ever heard of Wicca?

I’m sure you have. It’s that religion (yes - Wicca is a religion, with many sects) that Spirit Halloween and various Etsy sellers exploit so hard every autumn. It shows up in Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and Charmed, not to mention The Craft.

If you believe some of the older books about Wicca, published prior to the 1990s, you might be left with the impression that Wicca is a very old religion, dating back centuries, if not millennia. Most of the books outright said that kind of thing, and people passed the information around.

It wasn’t true, though. Wicca is, in fact, one of many new religious movements to take hold in the late twentieth century. It draws from many (slightly) older sources such as victorian occultism and the works of Aleister Crowley. Still, it was created in interwar Britain by a man named Gerald Gardner, working alongside others in the New Forest area of Great Britain.

Wicca, unlike Madrianism/Rhennish beliefs, was duotheistic. You can read a good guide to it, and a bit about how it developed and became what it is today, here from Catherine Noble-Beyer. I can’t speak to whether Gerald Gardner or anyone else ever returned to clarify that their original story about surviving covens of pagan witches was fabricated, but it definitely was. Most Wiccans in the 21st century acknowledge that.

Most pagans assume that Gardner told those stories as a way of presenting their (new) religion to the public in an appealing and non-threatening way, and also giving it a historical backing. I guess it could be similar with the Rhennes. So, were the Rhennes in Burtonport simply making up a pseudohistory worthy of Gerald Gardner to give their movement legitimacy?

Deceptions

The modern idolatry of physical "facts" as things-in-themselves is like worshipping sunbeams and denying the sun. Cut off from symbolic truth, this matter-worship creates a bleak and ugly world dominated by the machine and its soulless products. And this too is a symbol - of the spiritual state which has created it. - Sister Julia

The Coming Age, Issue 8, page 8, from 1978.

It’s clear that there’s no way they truly believed they were part of an ongoing, unbroken matriarchal tradition reaching back to those times, and had fabricated stories such as A Rhennish Childhood.

Many, many years later, a former member identifying herself as Soror Julia admitted this online quite plainly when explaining the (decidedly modern) origins of the Clear Recital, a document usually considered the Déanic scriptures. Soror Julia says that the Déanic scriptures were meant to reflect what the Rhennes saw as the Primordial Mythos, but that they were not channeled, per se. She goes on to discuss how they created the notion of small, surviving matriarchal communities in the British Isles, as well.

It was claimed that there were secret communities in Britain that had carried the tradition down the centuries from pre-patriarchal times. Those claims were quietly dropped later. I don’t think many people have even heard of them these days, fortunately.

Critical Apparatus to the Eastminster Library Edition of the Clear Recital, page 344, on Archive.org.

Soror Julia was only one voice, and speaking decades later online, as well. Her interview, which can be found in the Critical Apparatus to the Eastminster Library Edition of the Clear Recital on Archive.org, explains at least some of the (claimed) rationale for this, which is, frankly, more than we ever got out of Mr. Gerald Gardner, Wiccan. I guess?

On a purely factual level, of course it was a deception. It wasn’t in any way cynical or ill-intended. For my part, I had done a quite a bit of reading around ancient and modern religious traditions. It seemed that there had been many occasions when texts were attributed to great teachers, etc., without having been objectively written by them. I don’t think this sort of thing was ‘fraud’ in the sense that modern people would see it as being, with their heavy emphasis on things like individual authorship. It would mostly have been a matter of declaring one’s filiation to that tradition and a belief that one’s own individual authorship was of no importance. That is hard for the modern mind to accept, but it was the kind of thinking behind these claims. We were aware that we had no living tradition. We believed, or hoped, that we were representing something not too unlike—or at least a rendition for the modern mind of—a feminine spiritual tradition that we postulated to have existed in the past.

Critical Apparatus to the Eastminster Library Edition of the Clear Recital, page 345, on Archive.org.

Perhaps it wasn’t a con, at least not in the sense that we’d think of one typically. It is, of course, true that none of their facts check out, but what did they, themselves actually believe? True, none of the Rhennes had Rhennish childhoods, and no truly unbroken tradition of worshiping God as mother existed. They knew this at the time.

They did seem, though, to genuinely believe in a matriarchal prehistory of some sort, despite lack of evidence. This wasn’t unusual at all in the early 1980s, with some scholars still entertaining the hypothesis. Were their publications on ancient woman warriors and the degenerative cycles of history all knowingly fabricated, just like their Rhennish childhoods?

Soror Julia ultimately went on to echo the above-quoted aside in The Coming Age from back in 1978.

And of course I did not accept the vulgar association of ‘myth’ with ‘untruth’. I believed (and believe) that myth, far from being untrue, is truer than anything else. Mere material facts come and go. They change, they waft, they burst like bubbles and are forgotten. Building one’s life upon them is like building one’s house upon water. What endures is that which underlies material manifestation, which in material manifestation is expressed through Myth.

Critical Apparatus to the Eastminster Library Edition of the Clear Recital, page 348, on Archive.org.

Other writers, talking about ancient matriarchies, tend to speak in more general terms about “when God was a woman.” The elaborate stories of warrior empresses with specific names, stories of life amongst them and riding into battle with them - where does that all come from? It isn’t part of historical scholarship, and didn’t, clearly, come from there. It didn’t come from an unbroken, matriarchal Rhennish tradition. Was it invented like the latter, or…

In other words, were they lying to outsiders in their book when they talked about (for example), Amazonian Queen Colwyn, or did they actually believe it themselves? Regardless, where do these stories come from?

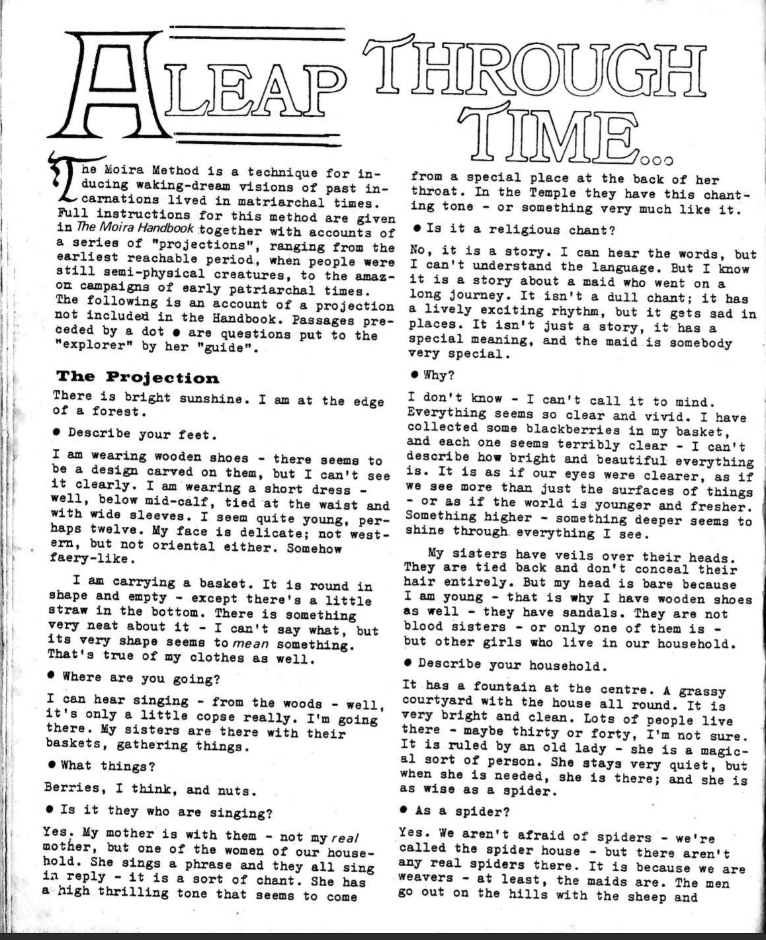

The Moira Method

The Moira Method is a technique for inducing waking-dream visions of past incarnations lived in matriarchal times. Pull instructions for this method are given in The Moira Handbook together with accounts of a series of "projections", ranging from the earliest reachable period, when people were still semi-physical creatures, to the Amazon campaigns of early patriarchal times.

The Coming Age, Issue 8, page 7, from 1978.

This Moira Method was implied to be the source of these stories, at least in The Coming Age’s issue on death and reincarnation (Issue 8, from 1978). I’ve found little about it outside of that, and certainly no copies of this handbook online. From the perspective of someone with a longstanding involvement in esotericism, the Moira Method seems to resemble many other, similar techniques designed to draw up memories of earlier incarnations.

Forty-ish years later, RJ, compiler of The Critical Apparatus to the Eastminster Library Edition to the Clear Recital speaking specifically on the origins of Déanic religion, wrote about this. RJ believes the fictional nature of these stories was widely-known and accepted amongst this early community. This is implied to include both recent accounts like A Rhennish Childhood. and the stories of the warrior empresses, etc.

Much of the confusion is probably attributable to Lux Madriana’s invention of what might be termed the ‘Rhennish legendarium’—a body of myths and legends tracing the history of Atlantis, Amazonian empires, and finally the ‘Rhennish culture’ that was their last direct inheritor in Britain and preserved their faith down to the present. These stories most certainly did suggest a long, wending trail of direct initiatory lineage, but belief in them as literal, material history seems never to have been a matter of obligation, and the authorship of many of them as fiction appears to have been widely known by members of the community. Sr Angelina herself is said to have been popularly known in Oxford as ‘Amazon Jane’ on account of a novel that she was writing. It may be that the legendarium was more or less openly meant as part of the creative development of the ‘body of Madrian stories and songs’ for which Sr Angelina called.

RJ, Critical Apparatus to the Eastminster Library Edition of the Clear Recital (p. 307).

I don’t want to share too much about my own life experiences outside of Aristasia, but I’ve been through similar techniques, including with another person guiding me. If I knew more about how they were going about it (rather than just the snippet transcript of the experience), I might be able to compare further. Either way, many people, pagan or otherwise, have experiences like this when delving into esotericism.

Assigning objective validity to them is a dicey matter, of course, especially when there’s reason to believe otherwise. I think, though, that some of what RJ (in Critical Apparatus) calls the “Rhennish legendarium” might’ve actually originated via these Moira Method sessions, rather than having been wholly, knowingly fabricated to give the movement a historical basis. It’s incredibly interesting to me to know that people writing fiction were involved so early on, though. Either the fiction inspired the legendarium or… the legendarium (albeit mythical) inspired the fiction?

Make of the Moira Method, and the stories about it, what you will. I can’t exactly try it, because I’ve been unable to find a digitized version of The Moira Handbook anywhere. I’m weird enough to give it a go if I did, though.

Onwards to Aristasia?

From the mountain's rayant pinaclé To the troubled watres of the sea, O Rhian, thy rule doth run As coursers of the sun: We pledge allegiance unto thee. We do pledge allegiance unto thee. We do pledge allegiance unto thee. We do pledge allegiance, O Rhiannë We do pledge allegiance unto thee.

The inside cover of Issue 18 of The Coming Age, published in 1981

On the inside cover of Issue 18 of The Coming Age, published in 1981 (see here) they printed the Rhennisleague Song, which is described as “one of the oldest Rhennish Anthems” (and arguably is).

The song, of course, is quite identical to the Aristasian Imperial Anthem as it was taught to me in the 2000s.

In The Critical Apparatus to the Eastminster Library Edition of the Clear Recital RJ, the book's compiler talks a bit about the stories circulating about “Rhennish childhoods” and whether they could possibly have any validity. The book mentions “an incident recounted by Miss Annya Miralene” about her (apparent) childhood amongst the Rhennes, presumably sometimes between 1913 and 1930. In this, a grown-up gives her a small spiritual lesson, involving a gramophone as a metaphor for Thamë.

The thing is, I’ve heard this story before, the involving the gramophone, the metaphor and kind lesson from an adult, all of it. It showed up in a lecture, if I remember right, that I listened to somehow in Aristasian spaces online, mid-2000s. If I can find which one contains the story, and if it’s preserved, I’ll link to it.

I know it’s anecdotal on my part, but it’s not an unfamiliar tale to me. Except, in the version I heard, it took place in Aristasia Pura, not in some kind of secretive community in our own world. I’m not sure what to make of that in the slightest.

If you’ve even a fleeting interest in Aristasia’s history, though, I do recommend you at least skim The Book of Rhiannë on the Internet Archive, though. It is extremely reminiscent of the Aristasian worldview… or perhaps it might be better to say that the Aristasian worldview is reminiscent of it.

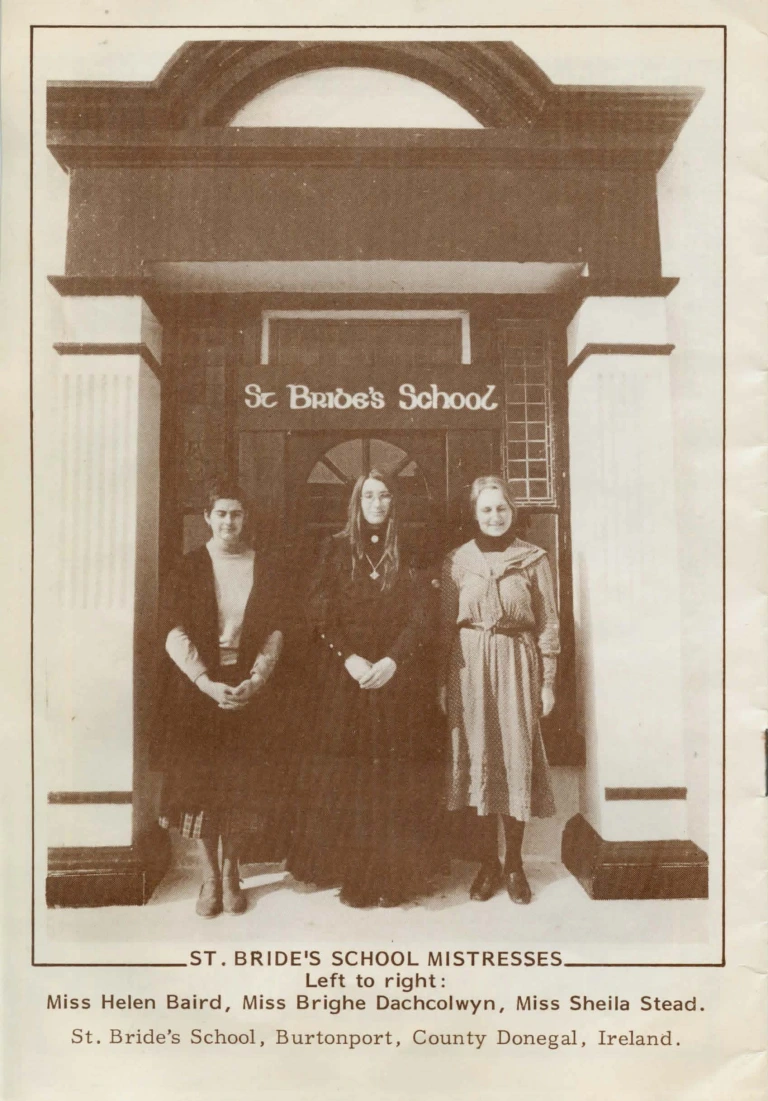

St. Bride's School for (Adult) Girls

This site already includes a blanket warning that it may contain links to, as well as discussion of, disturbing material. I want to, however, add a formal note here mentioning that the following section, discusses very real and quite apparent cult abuse occurring within an Aristasian precursor group.

When I tell people about the Rhennish commune and the Silver Sisterhood, their lifestyle, and all that, most agree that they would absolutely never agree to live like that. In fact, they say that it sounds utterly horrible. Might just be the crowd I run with, or a generational thing, but my friends all seem horrified by the idea of what living (or, rather making a living for oneself) would be like under such conditions.

The neatly-packaged bucolic image of a “Rhennish childhood” where a maiden crafts beautiful statues to sell really wouldn’t work properly under late capitalism, as most sensible people realize nowadays. This is why older (well, people my age) tend to laugh at some of the neopagans who suggest going off-grid to “escape the mundanes” and such.

So, what happened, and, quite pressingly, why do this, particularly past the point when such things start to obviously fail? Was the commune a cult-like setting? How did they (attempt to) stay afloat, ultimately?

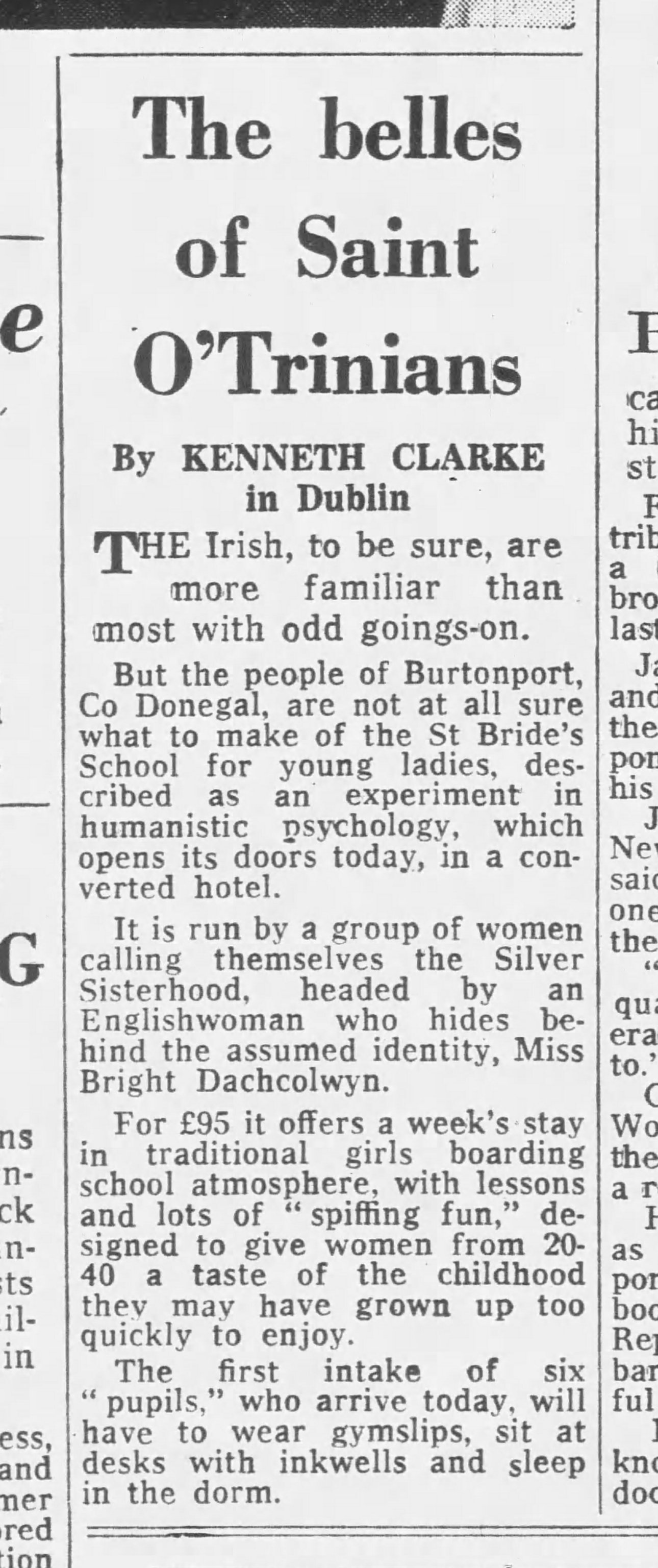

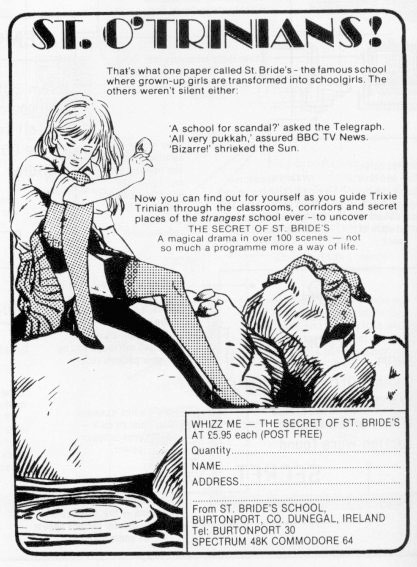

The women wore Victorian crinolines, long cloaks and bonnets, and covered up their faces with veils. And when they opened a holiday "school" for women, offering the chance to re-live schoolgirl romps such as picnics, midnight feasts in the dorm and canings, the Press had a field day. Says Helen; "We needed to raise funds so we advertised the fantasy role-play holiday."

Quotation from an article about the experiences of a woman named Helen Gilmour, part of both Rhennes and St. Bride’s School for (Adult) Girls.

The above quotation is from a newspaper article called “How I was Drawn into Life in a Cult,” which I’ve been unable to find in a scanned print form. It is primarily an interview with a woman named Helen Gilmour who, initiated into Rhennes, the Silver Sisterhood, ultimately left.

She here explains how the group began the enterprise known as St. Bride’s School. Not an actual school for children, this was a holiday retreat of sorts for adult women wishing to roleplay as children.

This doesn’t seem to have been a method of recruitment, nor for any particularly religious purpose, but because they struggled to survive within the bubble of their pseudo-Victorian lifestyle and needed a way to raise funds, or perhaps for reasons of, as discussed in the article on physical "discipline" within the movement, genuine sadism or cruelty on the part of those involved at the time.

This was, as the quotation alludes to, a holiday school where adult women roleplayed as schoolgirls in, ahem, as accurate a manner as possible, and did feature the inclusion of canings. On my article about “discipline” as a concept within Aristasia, I argue that this apparently (depicted as) financial endeavor (the opening of St. Bride’s School) marked the entrance of corporal punishment into the tradition as a whole, and I also believe that Helen Gilmour’s remarks support this position.

The group settled in a rambling old house in Ireland, and practised a form of goddess worship based on a female creator and female dominance on earth. Says Helen: "It was an organised form of religion but it was in some respects very disorganised. It was stressful."

She puts this down to the policy to reject modern machinery and technology. "It was supposed to be a traditional, rural farming community, but it didn't work. There was not enough land to run a farm and none of us was competent enough. We had a donkey and poultry and we dug the ground, but we weren't achieving anything."People had to appear busy, but had nothing to do. There was a spiritual malaise, a lack of discipline and organisation which ruined the community - it filtered down from the leadership."

Another quotation from the same article linked above.

Some ex-members refer to the Rhennish commune, particularly after it became St. Bride’s School, specifically as a cult. Helen Gilmour is quite frank about that, as the title of the article about her experiences makes clear.

Gilmour speaks of the religious aspect as prompting her initial involvement, though, and it was likely she joined during the era when the group was simply known as Rhennes or the Silver Sisterhood.

She went to a gathering of cult members. She recalls: "I didn't know what to expect. There were only five of us, but it was a moving ceremony. It had an impact on me. I was 29 and until then the only religious experience I'd had was as a child at the local Methodist church."

To the chagrin of her family, Helen, who lives in Great Horton, left her job with the Ministry of Agriculture and joined the 20-strong group full-time. She was initiated as a Lady of the Temple. She says: "It was like a confirmation and involved a 24-hour fast and all-night vigil."

Helen Gilmour speaking on the religious aspect of her involvement.

This will likely be a (or no?) surprise to most people, but nobody has ever come forward to speak to (for example) a journalist, etc, about having stayed at St. Bride’s as a holiday school. The school’s “headmistress” (in her interview with the BBC podcast on the subject in 2022) claims that the woman who later pressed charges against her for harming her during physical “discipline” came to the school for this purpose, but this is not supported by the testimony of the “maid” herself. I am inclined to believe the “maid” over the “headmistress” here, too.

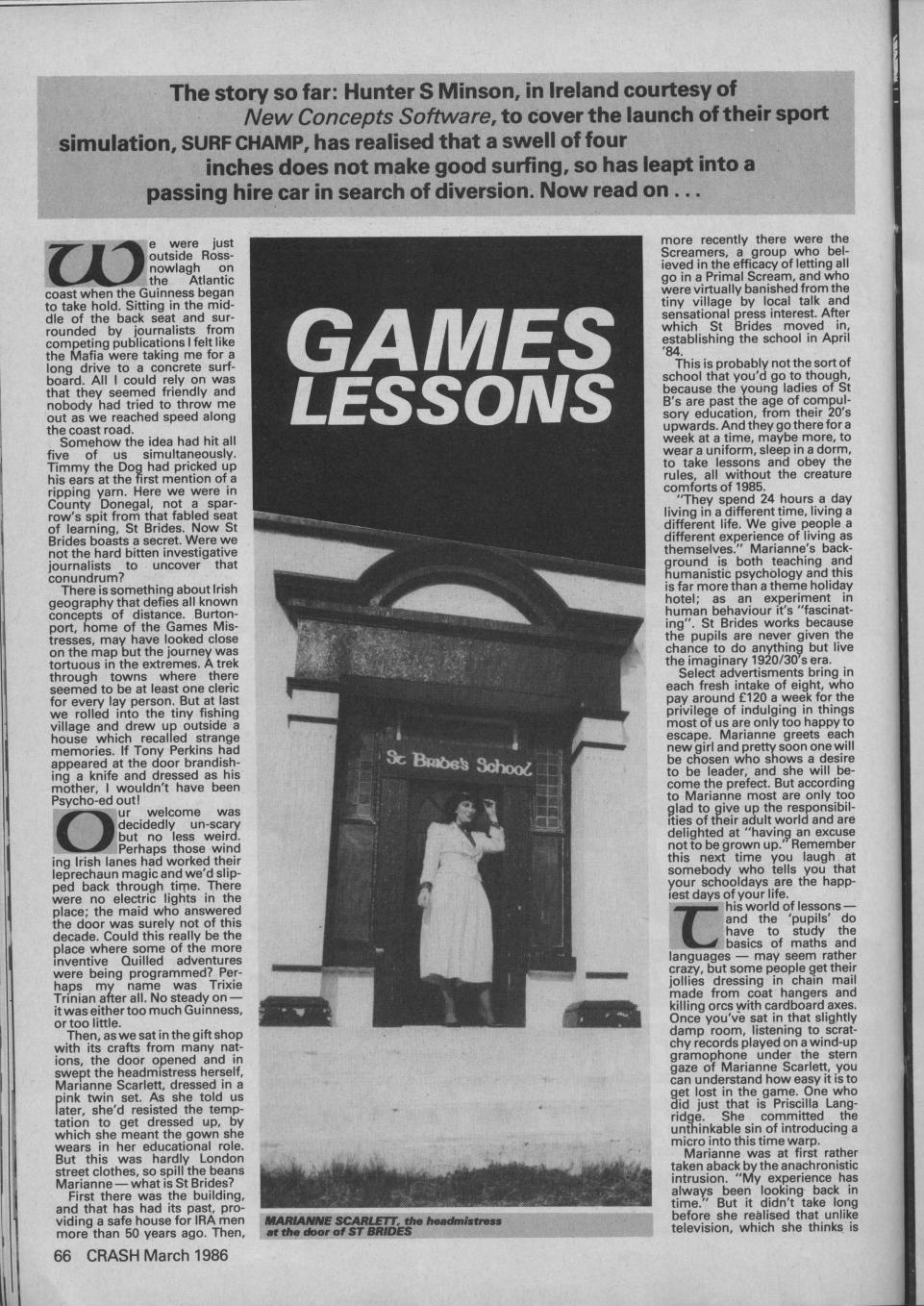

“They spend 24 hours a day living in a different time, living a different life. We give people a different experience of living as themselves.” Marianne’s background is both teaching and humanistic psychology and this is far more than a theme holiday hotel; as an experiment in human behaviour it’s “fascinating”. St Brides works because the pupils are never given the chance to do anything but live the imaginary 1920/30s era.

Select advertisements bring in each fresh intake of eight, who pay around £120 a week for the privilege of indulging in things most of us are only too happy to escape. Marianne greets each new girl and pretty soon one will be chosen who shows a desire to be leader, and she will become the prefect. But according to Marianne most are only too glad to give up the responsibilities of their adult world and are delighted at “having an excuse not to be grown up.” Remember this next time you laugh at somebody who tells you that your schooldays are the happiest days of your life.

This world of lessons — and the ‘pupils’ do have to study the basics of maths and languages — may seem rather crazy, but some people get their jollies dressing in chain mail made from coat hangers and killing orcs with cardboard axes.

From a gaming news article in 1986

The people "killing orcs with cardboard axes" tend to take a break from it, though, and I expect it was a rather different experience. If it were changed up a bit (perhaps only the fun classes, like art and playing soccer outside) and didn’t involve the canings that were happening behind the scenes, a holiday school with this premise doesn’t sound that bad, so a lot of news organizations covered the concept. The mayor of the town of Burtonport apparently turned up for the school’s opening.

Nevertheless, despite florid discussions of groups of girls supposedly flowing through the doors, no one outside of the core group who lived there has been able to say, “yes, I visited St. Bride’s on holiday.” Some press coverage claims a woman did come to the school for the “schoolgirl holiday” but brought a microcomputer, thus introducing computers and gaming to the world of St. Bride’s, and, ultimately, Aristasia.

Once you’ve sat in that slightly damp room, listening to scratchy records played on a wind-up gramophone under the stern gaze of Marianne Scarlett, you can understand how easy it is to get lost in the game. One who did just that is Priscilla Langridge. She committed the unthinkable sin of introducing a micro into this time warp.

Marianne was at first rather taken aback by the anachronistic intrusion. “My experience has always been looking back in time.” But it didn’t take long before she realised that unlike television, which she thinks is passive and mind rotting, computers “call for 100% concentration and commitment. They’re not just playing with a joystick.” So, about a year and a half ago part of St Brides entered the modern world, though they’ve been known to do their computing by candle light.

From the same gaming news article in 1986

This, too, seems unlikely, as many have pointed out. This wasn’t a girl bringing a smartphone on her short getaway. It was the 1980s, when microcomputers were insanely expensive and wildly difficult to cart around. I doubt someone would’ve truly lugged one to their “schoolgirl holiday” if that was why they were really there - all evidence points to this woman having already been a prior member of the group.

Given some of the things that apparently went on at St. Bride’s School, there’s very little to regret about people not showing up in droves for their “schoolgirl experience." More about that later. But first, let's discuss that microcomputer and how it changed this movement as a whole.

Gaming has entered the Chat

Regardless of the how of it, a microcomputer (as desktops were called at the time) did make it into St. Bride’s School. This began what would become a long-standing tradition within the movement of keeping up with the latest technology, one that would continue well into the late 2000s with games like Second Life, as well as numerous smaller video games.

It wouldn’t surprise me of the original impetus for programming the games had been financial to a degree. Helen Gilmour portrays the group as struggling with funds and resources, so this seems somewhat likely. Regardless, I don’t doubt that there were other influences at play as well.

Hardly a computer expert at that stage, she looked upon the micro as another medium, like books or comics, to be exploited as a rich experience — rather like the school. In fact the Secret of St Brides, their first adventure, set in the corridors and dormitories of the house, then out onto the cliffs, came from a game that they would play as they took the pupils on rambles. A mystery would be created from a few bare facts found as they walked along the shore.

Selling at first by mail order only, via a suggestive show of stocking tops and school uniform, Secret sold well enough to gather some good reviews and cement a proper distribution deal. It’s very much a standard Quilled product in form, though Priscilla claims to “like the economy of the two word input. People make a fetish of excess sophistication.” Its main strength lies in Priscilla’s writing skills, which are both witty and atmospheric.

Secret is also refreshingly different — there’s not an orc or an elf in sight. And it casts you in the role of a female character, though neither woman sees herself as carrying out a crusade for women in computing. “We’re not setting out with a market in mind,” Marianne tells me. Priscilla adds “We want the games to be open and accessible, to appeal to adventurers of both sexes.”

Spurred on by their success, the Games Mistresses, as they styled themselves, set to work on The Snow Queen, intended to be the first of a series of tie-ins with books in which it’s hoped that facsimilie editions will accompany the game. Snow Queen is based on a classic, dark fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen in which a girl seeks to save her brother whose view of life has been corrupted by a fragment of a mirror made by the devil. With it, the programming has become more sophisticated, so that Gerda appears to have a will of her own when it comes to obeying instructions.

From a gaming news article (Crash Magazine) in 1986

Either way, St. Bride’s School became a reasonably well-known publisher of text adventure games, which were used to promote (quite clearly) the “schoolgirl holidays” themselves (which might’ve been hypothetical - we don’t know that anyone actually signed up).

The controversies that had arisen surrounding the “school” itself were then, in turn, used to advertise the games, all, presumably, helping to keep the enterprise (of living, well… like that) afloat as best they could. Again, despite aggressive promotion, nobody’s came forward to any journalist or with any account (outside of obvious “life theatre” from the inner circle) about having stayed at the school as a guest.

We do know that plentiful people played their video games, though, leading to a situation where the strange group was often interviewed and visited by the gaming press. Women in Victorian garb, yet coding strange video games by candlelight does capture the imagination, doesn’t it?

Things were worse inside the school than one might’ve imagined, though…

Bruises and Welts

For more context about this and other physical "discipline" and abuse-related issues surrounding Aristasia, visit the designated page.

WELTS and bruises were found on the buttocks and thighs of a pupil of a school run by a group called The Silver Sisters in Burtonport, Co. Donegal, after she was chastised by the principal, Dungloe Court heard yesterday.

The court was told that St. Bride's School was run along Victorian lines and that the pupil, Ms. *REDACTED BY WEBSITE*, who was 21 at the time, was stripped and lashed with a birch for breaking the school rules.

Ms. Maria da Colwyn, the principal, was given a two-months suspended jail sentence by Justice Liam McMenamin for assaulting Ms. *REDACTED BY WEBSITE* on November 7, 1989. Describing it as a case of "irrational behaviour", he also fined the defendant £100, commenting that this would get back some of the legal aid Ms. da Colwyn had received. Neither the defendant nor the complainant was in court.

The court heard that Ms. *REDACTED BY WEBSITE*, who went back to England with her father after the incident, fled to the local garda station for sanctuary after being birched by the defendant.

She was subjected to degrading behaviour, her underclothes were stripped off and she was lashed with a birch by the principal, Supt. Eamon Courtney said. She had to bite her lips to avoid screaming.

A ban-garda who examined her found welts, bruising and discolouration on her thighs and buttocks.

Ms. *REDACTED BY WEBSITE* alleged that this was the third beating she had received and that in previous punishments she was hit on the top of the thighs with a cane. After being beaten she lay quivering on the bed, she told gardai.

Supt. Courtney said that at St. Bride's School even minor breaches of the rules, such as spilling ink, resulted in birching. Ms. *REDACTED BY WEBSITE* had been at the school for over a year and while she knew there were certain rules, the chastisement was never spelt out to her, he said.

He added that the fees for the school, as advertised in the English tabloids, were £95 per week and that eight to ten pupils attended it at a time.

Mr. Patrick Sweeney, the defendant's solicitor, said that within the community at St. Bride's, corporal punishment was used, and the defendant did not feel she was breaking any laws.

Justice McMenamin said he would deal with the case in the same way as he would deal with an incident of this type in an ordinary national school.

"Silver Sisters Pupil Stripped and Birched," Irish Independent, Wednesday, February 13, 1991, page 13 referring to Marianne Martindale (here Ms. da Colwyn)'s court proceedings in the 1990s.

It would certainly seem from the Irish Independent that things had gone quite wrong at St. Bride's School. While the Sunday Mirror may not be the best journalistic organ in the United Kingdom, it published the below spread on this, as well. You also find this covered in a podcast done by the BBC quite recently. All describe horrific abuses inflicted upon the young girl acting as “maidservant” at St. Bride’s School, particularly by Marianne Scarlett, the “headmistress” of the institution.

“Things went wrong when Miss Rayner left and I was taken under the wing of Mistress Scarlett. That was when the beatings started. If I answered back of did the slightest thing wrong, she’d say she would punish me. But she would never say when. Every time she called be I would be terrified that I was going to get the cane or birch but she would leave me hanging on for hours or days. She would take me to my bedroom and make me lie down on the bed, lift my underclothes and cane me on my bottom or the tops of my thighs. Or she would take me to a mock classroom and make me bend over a desk and cane me on my backside. I had to apologise for my misdemeanour, thank her for my punishment, curtsey, and leave the room. I had been brainwashed into their way of life. I hated the beatings, but I didn’t think anything was wrong. I used to hear Mary Scarlett shouting at Priscilla at night and Priscilla whimpering in a little girl’s voice. Then I would hear the swish of the cane and Priscilla’s cries.”

The aforementioned Sunday Mirror article, from March 11th, 1990.

When asked by the BBC if she has any regrets about her interactions with the maid, the “headmistress” (Mary Scarlett, who now goes by another name) said that she absolutely does not, displaying, in my opinion, a startling lack of empathy.

Prior to rather recently, this particular article hadn’t been digitized - or, at very least, wasn’t made available to me or most of the 2000s Aristasian online crowd.

We were, via Wikipedia and other quite general sources, aware that there had been legal action that resulted in a conviction as a result of “discipline” activities in Aristasian precursor groups like St. Bride’s School. This was, naturally, downplayed as much as possible by inner circle Aristasians and those in control of related websites. I don’t recall much mention of it at all from internal sources.

I, and others, though, knew the history of Britain, its sexual “morality” and attempted legislation thereof. I figured this might’ve been a case where there hadn’t even been a real lack of consent. Sometimes accidental injuries, for example, can prompt mandatory criminal charges, or so I’d heard. Weirder stuff has happened to queer people, when The Straights start clutching their pearls.

It seems that others made a similar assumption, though no one specifically told us such. How utterly wrong we were, it seems.

National Front and Fascist Ties

This section discusses the (very apparent) fascist ties at St. Bride’s School. You can find some more about that here. I do want to state as plainly as possible: fascists of any sort are unwelcome on this site. This includes the alt right crowd, anyone fancying themselves “neoreactionaries,” etc.

Sometime around Christmas of 1993, the group living at (and presumably attempting to run) St. Bride’s School, had apparently ceased paying rent and relocated. This left a situation wherein the building’s owners, the Atlantis Commune (yes… the “primal screaming” advocates), attempted to regain control of the building itself. They did this by breaking in, as is often the case when similar situations with tenants and such arise.

Anne Barr, 36, and Mary Kelly, 40, found material produced by neo-Nazi organisations and the sado-masochistic sex industry. Anti-Semitic periodicals from all over the world lay in piles on the floor, alongside fetishistic magazines featuring women in gas masks and suspenders and price lists for equipment such as handcuffs and leg-irons. Titles strewn around included National Front News and the British National Party's Spearhead.

To judge from printed forms called "Caning Recommendations", education in St Brides seems to have involved regular beatings with cane, birch and even nettles. The sisters used desk-top publishing to print their own magazines - some of them admired in literary circles - such as The Romantic, a whimsical publication illustrated with silhouettes of ladies with parasols and columns such as "Pippa's Pipsie Page" and "Parlez-Vous Romantique?".

Most surprising, among letters from Irish farmers enquiring whether bondage and domination were on offer at the academy, was evidence of a two-year correspondence from the British National Party leader, John Tyndall, who seems to have found much in common with the sisters' dislike of the present and who put them on the mailing list for the BNP magazine Spearhead.

In one letter, Mr Tyndall, talking about politics, says: "I admire and respect what you are doing to the point of fascination" and says he agrees entirely that there should be secession from the modern world. Of himself, he says he is "spiritually with one foot in the 19th century and the other in, perhaps, the 17th and 18th".

The Sunday Telegraph, January 3rd, 1993

I was vaguely aware during my time participating in Aristasia that someone associated with this precursor group had possibly corresponded with someone from the British National Problem in the distant past; I wasn’t quite sure what the BNP was when I first found out about it. I had to have been about fifteen or sixteen, but it’s hard to say. I did eventually google around and realize that the British National Party actually did and believed, it was upsetting, to a degree.

Still, they provided excuses of various sorts, or at least, their proponents online did. I myself didn’t assume, nor expect such a close association, though, but rather overlapping social circles. This made me think of that old diagram that says that things get closer together depending on how far one is from the “norm.” This didn’t seem that unusual, sadly, in esoteric and fringe communities. I also readily assumed that St. Bride’s School had actually had regular guests, too - not just the original Rhennish commune themselves, which was likely untrue.

In any case we, (as in, former online Aristasians) learned more about the situation later, from articles like the one linked above. This painted a decidedly different picture of the situation. The full picture really hasn’t come together for me as of yet, as far as I’m concerned, about St. Bride’s School, or Aristasia itself. We can easily see its beginnings in these articles, after all.

A woman calling herself Laetitia Linden Dorvf, installed in north Oxford in a house she calls The Imperial Embassy, was cagey about Miss Tyrrell. Her people could not be categorised under individual names. She acknowledged the court case but claimed the girl was caned as part of a disciplinary session to which she "quite voluntarily agreed".

But she denied that the sisters had links with the publications found in their house. "We do not endorse any of them as they are all collaborating with the degeneration of the late 20th century. We simply receive them as part of an exchange subscription. One of our girls was in correspondence with the National Front and we may have a copy of National Front News in St Bride's.".

The Sunday Telegraph, January 3rd, 1993

The reference to not being categorized under individual names is likely an early variation of the Aristasian perspective on the self, where a girl had many personae or manifestations. We also, in this same article from The Sunday Telegraph, see the beginnings of the movement’s usage of “discipline” itself as (at very least) a public financial endeavor.

They had set up a pay-per-hour phone line for “lessons” from a stern teacher named “Miss Partridge.” This trend of offering what they claimed to be non-sexual disciplinary services to stay afloat continued throughout the 1990s, as I’ll talk about later.

One of the sisters has now set up an 0898 phone line that offers men and women lessons from a lady teacher carrying a cane at £75 and hour. Describing the activities, a "Miss Partridge" says: "I shall not hesitate to tell you to stand up and bend over the desk if I am at all displeased." She adds: "It is not in any way a game. There is nothing in my lessons which is immoral, immodest or improper." Yet Miss Linden Dorvf said the sisters loathed everything connected with the late 20th century. "We have totally seceded from this period. It is a howling desert. We don't watch television or read newspapers. We considers the output of BBC1 to be totally lewd and unsuitable."

So what about the tape? The phone number did, she said, correspond to her house. "It is not my department. I would like to stress that what is being offered would not involve any sort of immorality. We condemn any sexual activity outside marriage."

Miss Partridge, the enthusiastic disciplinarian could, Miss Linden Dorvf said, be "many people".

Was it possible that she, Miss Tyrrell and Miss Partridge were one and the same? Certainly their voices were similar.

She neither confirmed nor denied it. "We like to cultivate different personalities here, you see."

The Sunday Telegraph, January 3rd, 1993, quoting a “Miss Linden Dorvf” associated with St. Bride’s School.

Returning though, to the matter of Miss Tyrrell’s association with the British National Problem, though there were several sites (made by those, it would seem, other than the core group) in the early 2000s. They argued that St. Bride’s had received “fan mail” from John Tyndall, perhaps unsolicited. One even speculated that Tyndall might’ve had prurient reasons for writing to them.

For quite some time, this seemed perfectly possible to me. It was probably quite easy to end up on dodgy mailing lists, just as it is nowadays, especially if you’re fringe in any way. Back then, those were physical mailing lists, since the internet was still in its infancy, of course.

When the Sisters left their Irish HQ in December 1992, the people from whom they had rented the building found it strewn with anti-semitic magazines, as well as a sheaf of friendly letters to Miss Tyrrell from the British National Party's leader, John Tyndall. There were also price-lists for leg-irons and in- struments of torture. The house's owners then discovered that two years earlier, under the name of Mari de Colwyn, Miss Tyrrell had been convicted of actual bodily harm. for caning a girl on the buttocks.

After fleeing from Ireland, with her rent unpaid, Miss Tyrell turned up in Oxford. From her new base off the Iffley Road, under the pseudonym "Miss Partridge", she advertised in the Oldie: "Strict governess gives genuine traditional lessons." Callers were told that for £75 an hour they could be instructed by a stern female pedagogue. "I shall not hesitate to tell you to stand up and bend over the desk if I am at all displeased," she warned. Later in 1993. the same Oxford telephone number appeared on an advert in the New Age Review: "Born out of Time? Romantia is a magical Kingdom outside the late 20th Century. Tel: Countess Rassendyll..." For a mere £12, the "Countess" offered a year's subscription to her magazine, the Romantic (which "comes out sporadically"), and to two other periodicals she edited, Imperial Angel and the English Magazine.

Are the Countess Rassendyll, Miss Partridge, Mari de Colwyn and Miss Clare Tyrrell by any chance related to Marianne Martindale? “It rather depends,” she told me this week. “We rather share our names round a bit.” When pressed, however, she admitted that “Miss Tyrrell in Ireland was one of my manifestations”

The Guardian, March 1st, 1995, discussing the events in Ireland and after.

That sure sounds a bit different than just ending up on a mailing list and getting some fan mail…